News and Opinion

Gokan no Hiroba

As part of my current research in the history of Japanese film theory and criticism, I met with the great film critic, Yamane Sadao, last week. Since I had just watched a press screening of Sakamoto Junji's new film, Zatoichi, the Last, we met in a cafe in Hibiya.

Since I had a bit of time between the screening and the meeting time, I wandered around Hibiya. That area around Chanter is basically Toho territory, developed in the 1930s by Kobayashi Ichizo of the Hankyu Railway (now all part of the Hankyu Hanshin Toho Group) . The home office is there, as are some Toho theaters and corporately related theaters (such as the Tokyo Takarazuka Theater). Even Chanter, a shopping center, is owned by Toho.

In front of Chanter is a square that in Japanese is called the "Gokan no hiroba" (合歓の広場), which roughly translates as "Entertainment Square" ("gokan" is a rarely used word meaning communal enjoyment). Since this is Toho terrain, there is a statue of Godzilla and bronze hand prints (in relief) of some famous movie stars. Most of the stars are Toho veterans, such as Mifune Toshiro, Morishige Hisaya, Frankie Sakai, Yamaguchi Yoshiko (Ri Koran), Ueki Hitoshi, Nakadai Tatsuya, Tanba Tetsuro, Kayama Yuzo, Takamine Hideko, Ikebe Ryo, etc. But there are other stars such as Misora Hibari and foreign stars like Jackie Chen and Tom Cruise. In addition to the hand print, for each one there is usually a signature and a comment.

Some (Re)Visions of Japanese Modernity

It took a while, but I am very glad to announce that my new book, Visions of Japanese Modernity: Articulations of Cinema, Nation, and Spectatorship, 1895-1925, is finally out and available at booksellers like Amazon (you can also get it straight from the press). I would like to thank everyone, including those at the University of California Press, for their patience and support.

This took a while to realize. The first version was my dissertation, submitted over a decade ago. A lot has happened since then, including three other books and multiple jobs, but this work continued to change and evolve. Some of the original chapters got published elsewhere and disappeared from the manuscript (the one on novelizations and film criticism ended up in Word and Image in Japanese Cinema; the section on national cinema ended up spread out between A Companion to the Anthropology of Japan and The Culture of Japanese Fascism

); remaining chapters were refined, revised, and updated. It's inevitable that an author thinks more could have been done here and there, but people have waited long enough, and sometimes you just have to let your baby leave the nest.

Theater Kino in Sapporo

I was surfing the internet the other day and found myself. My wife and I visited Theater Kino in Sapporo at the beginning of the year (my wife is from Hokkaido) to watch Waltz With Bashir (which by the way should have won the Academy Award for best foreign language film, not Departures

). Theater Kino is Sapporo's only real independent mini-theater showing alternative and art house movies. The first Theater Kino was founded in 1992 and only had 29 seats; the new one started in 1998 and has two screens, one with 63 seats, the other with 100. It is now located on the second floor of a newly built office building.

It has a nice atmosphere (here's the Cinema Street introduction), if only because the lobby is covered with graffiti written by many of the big people in Japanese independent film (and some foreigners too). It's fun just to find and read what's written there. They also have set up a used book corner, which provides the warmth of printed paper. Plus they have Billiken (from Sakamoto Junji's film) protecting the theater:

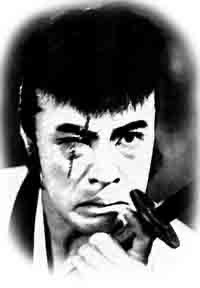

Nishikawa Katsumi

The news services report that Nishikawa Katsumi, the director of many of the great postwar youth films, died on April 6, 2010, of pneumonia. He was 91.

Nishikawa was born in 1918 in Tottori and graduated from the Arts Faculty of Nihon University before entering Shochiku in 1939. The war interrupted his career - an experience he would later write about - but he returned to being an assistant director to Shibuya Minoru and Nakamura Noboru before directing his first film in 1952. He switched to Nikkatsu in 1954 when it resumed production, making films in a number of genres - including action movies - but it was his youth films starring Yoshinaga Sayuri (Nikkatsu's eternal virginal star, with fan sites here and here) or Takahashi Hideki that proved to be big hits. He moved to television when Nikkatsu turned to Roman Porno, but he returned to film in order to shoot youth films starring Yamaguchi Momoe (the enigmatic idol star of the 1970s: see here and here and here) and Miura Tomokazu (whom Momoe-chan would later marry), including such movies as Izu no odoriko (The Izu Dancer) and Eden no umi that he had shot at Nikkatsu before.

Iconics 10 and Academic Film Societies in Japan

Film studies has had a hard time developing as an academic discipline in Japan. There are many reasons for that, but one has been the lack of a strong film studies society. Such societies can be problematic in the way their power can be used to define the discipline, but when the discipline is in the minority, they can be strategically important in coordinating activities, promoting communication and networking, consolidating power, and providing legitimacy.

The Japan Society of Image Arts and Sciences (Nihon Eizo Gakkai 日本映像学会) has valiantly tried to create such a society in Japan, but it has not been easy. Academic societies in Japan need a university to back them, but the JASIAS's backer, Nihon University, insisted from the start that film was insufficient for an academic society and forced the founders to make this an eizo gakkai not an eiga gakkai. The JASIAS is still hampered by having a membership that is too diverse, spanning film academics to filmmakers, from educational media consultants to people who make video projectors. The film studies people, however, long ago "took over" the two journals the JASIAS publishes - Eizogaku and Iconics - and now these two can offer some of the best examples of academic film scholarship in Japan. (I have been a member of the JASIAS for about twenty years, including several years serving on the board of directors, and many years working on various committees, including the editorial boards of the two journals.)