News and Opinion

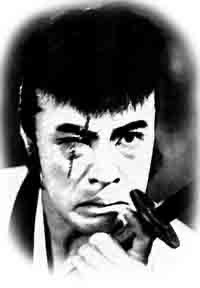

Saito Koichi

The Asahi reports this morning that the film director, Saito Koichi, passed away on November 28th or pneumonia. He was 80 years old.

Saito-kantoku was one of the more unique directors in Japanese film history who deserves more attention than he has gotten. First, after studying at Rikkyo and then the Tokyo College of Photography (now Tokyo Polytechnic University), he started out as a still photographer, at Oizumu Eiga (one of the precursors of Toei) and then at Nikkatsu. He was one of the unsung figures who defined the Nikkatsu Action style: many of the cool stills you see of the Nikkatsu films that are finally getting released outside Japan were shot by him. He also did stills on films by directors such as Imai Tadashi, Imamura Shohei and Ichikawa Kon. He would be a central figure for anyone writing a history of Japanese stills photography (a history which should be written some day), and a fascinating case where stills began to effect the style of the films themselves.

Saito-kantoku has a quite cool, modern visual sense, so when he decided to direct his own film, gathering enough money to make Tsubuyaki no Jo in 1967, the result was an urban, pop masterpiece that resembled more Richard Lester's Beatles than anything in Japanese film, albeit with more pathos. He and perhaps Obayashi Nobuhiko (in his 1960s experimental films) were arguably the first to really adapt that kind of commercial 1960s visual sense to Japanese film. Saito then utilized that sense in a series of "Group Sounds" films at Shochiku in the late 1960s, which are all quite interesting to watch, especially Chiisana sunakku, based on the Purple Shadows' hit.

Tenth Tokyo FilmEx Symposium: Towards the Future of Cinema

I've been busy with Tokyo FilmEx this week, Tokyo's best film festival (the slap against the TIFF is intentional). It opened on Saturday, November 21, with its annual symposium, this time dedicated to the theme "Towards the Future of Cinema." The guest list was impressive: Kitano Takeshi, Kurosawa Kiyoshi, Koreeda Hirokazu, Nishijima Hidetoshi, and Terajima Susumu. But unfortunately, the event didn't get very deep into what could be the future of cinema in Japan.

The first hour was a "master class" with Takeshi, who was interviewed by Yamane Sadao and accompanied by his producer, Mori Masayuki. He didn't talk about much that he hadn't mentioned in previous interviews, or that I hadn't discussed in my book on him. But he did drop one bombshell (Yamane-san and I agreed on that afterward): he suddenly declared that his work on TV involves no compromises, but that he has been compromising with film all along. This stunned Yamane-san and even prompted a response (his only statement in the event) by Mori-san: hasn't it been the other way around with Takeshi? But Takeshi insisted this time that since TV can be viewed for free, he could do anything he wants, but since people pay to see films, he has had to compromise with the audience in mind. This reminded me a bit of his logic for why Zatoichi is a different film: since this was a project for hire, he had to do a decent job for those hiring him. But it doesn't hold water: TV may be for free, but viewers are sold by the networks to advertisers, and thus the variable measure of viewers - ratings - is central to the payment system that pressures performers. Takeshi's statement reinforced my sense that he can be moody at times and can say quite different things about his career depending on that mood. This, it seems, was not a good time and he spoke badly of most of his films. He mentioned that his new movie will be a yakuza film - as if returning from where he got started - and again may involve the death of his character (he mentioned this while criticizing Eastwood's Gran Torino

), but in a cast composed of newcomers to his cinema. The only time he got onto the symposium topic was when he mentioned that new editing technologies are making the editing process much faster, which is convenient but problematic: he prefers time to think when editing.

Mizonue Takiko

The morning papers are reporting the death of Mizunoe Takiko. She died of old age on November 16th at the age of 94. Most people remember Tākī, as she was fondly called, as a star of the Shochiku Shōjo Kagekidan (Shochiku's rival to Takarazuka), where she in the 1930s she stunned fans as "the beauty in men's clothes." She joined it in 1928 at the age of 13 and left in 1939 to start her own troupe. She was also famous after the war as a host of Kohaku utagassen (the Red and White Song Competition) when it was still on radio and then on TV, and as one of the team leaders on NHK's long-running TV game show, Gesture.

But we should remember her as a dynamic film producer in an age when almost all the producers were male. She produced Taiyo no kisetsu (Season of the Sun) at Nikkatsu and is widely credited for building Ishihara Yujiro into a star (I wonder if the Kitahara Mie character in Arashi o yobu otoko is not based on her). She produced his first starring film, Kurutta kajitsu (Crazed Fruit, which Criterion has put out on DVD), as well as many other of Yujiro's films. The JMDB lists her as producer on 76 films, all at Nikkatsu.

Kitano Meets Obama

The evening edition of the Asahi is reporting on President Obama's first visit to Japan since assuming office. As part of his short visit, Obama made a major policy speech at Suntory Hall. Putting aside the content, one thing that was interesting was that Obama's staff strategically invited people of different kinds of importance, something significant enough that the Asahi had to report on it.. There was the mayor of Nagasaki, a city that suffered from the atomic bomb; the mayor of an Okinawan city, which is suffering from American bases; and even the parents of Yokota Megumi, the Japanese girl who was kidnapped by North Korean agents. There was also the mayor of Obama City, which has done its best to promote its accidental relation to the president. All these invites can attract their own little articles - and thus favorable publicity - here and there in the Japanese media. But essential in Japan, and especially in the Japanese media, are tarento, the fuel that makes the entertainment system run. And so a number of personalities were invited, including Puffy, Jero, and Motoki Masahiro, the star of Departures

(Okuribito).

David Bordwell on Research Guide to Japanese Film Studies

David Bordwell, one of the great film scholars writing on one of the great film blogs, said some kind words about our Research Guide to Japanese Film Studies.

Morishige Hisaya

On the top of the front page of this Asahi this morning was the article reporting the death of Morishige Hisaya, one of the most important performers of the postwar era. He died on November 10 of old age; he was 96. This was such big news, the newspapers put out an extra.

Morishige was born to a wealthy family in Osaka in 1913, and his characters often reflected a well-bred, witty, refined, but also a bit insouciant figure with a touch of pathos. He went to Waseda and did theater there, entering the great musical comedian Furukawa Roppa's troupe after graduating. But to avoid going to war, he applied for and got one of the most difficult jobs there is to get: an NHK announcer. From then on, Morishige was famous in part for his smart and mellifluous voice. He was sent by NHK to Manchuria, and it was his experiences there, especially escaping the country with his family after the war, that he said hardened him greatly and gave him a foundation for his later work.

Morishige only became famous as an actor in the early-1950s, and first as a great comedian, starring in many of the hilarious Toho comedy series such as the "Shacho" (Company President) and "Ekimae" (Station Front) series. There he played the spoiled but still lovable company president or official against such splendid actors as Frankie Sakai, Ban Junzaburo, Kobayashi Keiju, and Kato Daisuke. But Morishige's range was great, and in the mid-1950s began appearing in much more serious roles on film, such as the "Jirocho sangokushi" series (his Ishimatsu is rightly celebrated), Meoto zenzai, Neko to Shozo to futari no onna (based on a Tanizaki story), Snow Country

, and some of the best Kawashima Yuzo films such as Aobeka monogatari and Gurama-to no yuwaku. Everyone knows him in Japan, but he is less famous abroad because he did not appear in the films of canonized directors, with the exception of a small role in Ozu's The End of Summer

(as Isomura). He also starred on stage, often with his own troupe, repeating some roles hundreds of times (his most famous stage role was as Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof); he was also a prominent face on television, where he appeared in famous dramas and variety/talk shows. With his great voice, he also recorded many songs and did many recitations in public and on radio.

Japan Foundation "Scandal" Again

The reaction to my previous post on the supposed scandal at the Japan Foundation has been quite positive, so I thought I would update everyone on some of the discussions that have ensued.

There were a number of reactions on KineJapan, with Mark Roberts in particularly asking the crucial question of what may constitute the structural reasons behind the suspicious contracts. Part of the Asahi's laziness was in easily laying blame on the JF, but not asking how it is that film companies can get away with asking for such contracts. To Mark,

Actually, this seems like an opportunity to air out this relationship and, if necessary, publicly interrogate the constraints imposed by the rights holders and the government stance that tacitly supports them. Isn't it equally possible -- and actually rather likely -- that the rights holders have all the cards, and that taxpayers are being asked, in effect, to subsidize their exclusive ownership of Japanese film heritage? And where is the Japanese government in all of this? Standing on the sidelines?

Japan Foundation Scandal?

This appeared a few days ago, but the evening edition of the Asahi on October 31 reported something about the Japan Foundation (JF) that concerns many of us who like Japanese film. I wanted to mention this not only because of what was said about the JF, but also about the tone of the article, which I found disturbing.

As many of you know, the JF is involved a lot with promoting Japanese film abroad. They help fund events and festivals and researchers. Some of us take advantage of their "collection" of Japanese films with English subtitles to show at our organizations (though with these films we still have to pay the copyright owner for each screening), and some of us watch films shown at JF offices or Japanese embassies abroad.

I have noted in the past problems with the JF, which includes the fact that they don't make their list of films public. What the Asahi reported seems to concern mainly the cases when the JF has been showing films at JF offices and Japanese embassies. The JF has contracted with the producers and distributors of hundreds of films to show these works a certain number of times at these screenings. They make a list of these films and distribute it to their offices and to embassies for when they want to show films. The gist of the Asahi article is that some 90% of the films they contract for are not shown the contracted number of times before the contract expires, which means that money is being paid to distributors for screenings that never take place. Some contracts are renewed even though the film has not even been shown once. The paper declares this is a waste of the taxpayer's money totaling some $900,000.