News and Opinion

Yubari: Coal, Cinema, Kitano, and Caramels

After toiling for several months with loads of work, including teaching my Yale Summer Session class and doing a final check on my next book, I finally got my first vacation in ages. I went up to Hokkaido to rejoin my family at my wife's family home near Sapporo.

One of the things we decided to do was to venture up to Yubari, which is about an hour and half away by train (if you are lucky: so few trains go to Yubari that some itineraries take three hours. Going by car or bus may be best in some cases). Those of us in the film world know Yubari through the Yubari International Fantastic Film Festival, a winter-time festival that has historically combined some foreign film biggies with a few Japanese indies.

But Yubari was first and foremost a coal mining town, so when the mines closed around 1990, the city faced a serious problem. It first tried to maintain itself through the high-class Yubari melons, but that was not enough. The film festival helped (a lot of towns in the late 1980s and early 1990s, like Yamagata, started film festivals as a way of sparking the local economy and culture--machiokoshi, as it is called in Japanese). But the city also took advantage of government funds and borrowed a lot to build museums, theme parks, and anything else it could to attract tourists. But they didn't come. The result was that in 2006, the city went virtually bankrupt, city services were slashed, many of the attractions were closed, and the Film Festival was cancelled (and revived the next year thanks to NPO support). To many in Japan, Yubari is now synonymous with local government excess and mismanagement.

Matsubayashi Shūe

The Asahi reports this morning that the director Matsubayashi Shūe passed away on August 15th at the age of 89. The son of a Buddhist priest, Matsubayashi studied at Nihon University before entering the Toho Studios in 1942. He joined the Navy during the war, becoming an ensign, a position in command that provided him the background for many of the war films he directed after the war, including Ningen gyorai Kaiten (1955), Storm over the Pacific (1960), The Last War (1961), and Rengo Kantai (1981). He rejoined Toho after the war, eventually debuting as a director in 1952. In addition to war films, he also specialized in comedy, helming many of the "Shacho" or "Company President" films. His critical reputation usually focused on his Buddhist background to find moments of "emptiness" in his war films, but in general his war films emphasized the professionalism and sacrifices of wartime Navy officers. I have an article coming out on cinematic representations of the Battleship Yamato, which includes a section on Rengo Kantai.

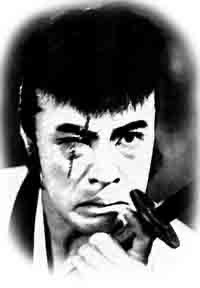

Yamashiro Shingo

The papers and TV are reporting that Yamashiro Shingo passed away on the 12th at the age of 70. He had long been suffering from diabetes. Yamashiro came to fame during the heyday of Toei jidaigeki, starring in such series as Hakuba doji (on TV and film) and Yagyu bugeicho, He easily made the shift to yakuza movies and was a featured player in the Battles without Honor and Humanity series. He later became very popular on TV as a host and panel member on many variety shows. He was married twice to the actress Hanazono Hiromi, but the relationship was apparently strained enough that their daughter, also an actress, was not even with him when he died.

Two things, I think, made Yamashiro stand out a bit. First was his love of film. Yamashiro penned a number of books of film criticism and hosted a TV movie show, as well as directed nearly a dozen films, including one of the bigger budget Nikkatsu Roman Porno movies, Meneko (1983). The second was his dedication to the cause of burakumin, the outcast caste in Japan that has suffered much discrimination. He often spoke about the entertainment community's discrimination against that caste and other minorities.

Nikko Edomura Utsushi-e

I took my summer session students to Nikko last weekend. We of course visited Toshogu and stayed at a nice hot springs inn, Tsurukame Daikichi. But as we did last year, we also visited Nikko Edomura. It's one of those "history" theme parks, this one set in Edo-era Japan. While it does give you a sense of what it might have been like in the Edo period (it does have some small museums on things like sword-making, etc.), it is less an accurate living history park than a kitschy recreation of a commercial image of Edo and should be enjoyed as such. It does have an open set for filming, but when I went there last year, that was all run down and not worth the trek up the hill. The main attractions are the various theaters, the ninja houses, and the characters running around on the streets. Edomura seems to be putting a lot of effort into staying alive (especially after Nikko Western Village went under), so there appeared to be more going on than even last year. Everyone had a fun time.

What was a very pleasant surprise for me, however, was the fact that one of their theaters, the Ryokokuza, was doing utsushi-e (for more on utsushi-e, check out this site by Kusahara Machiko). Utsushi-e, sometimes called gento, is the Japanese version of a magic lantern show that was very popular in the 1800s and a historical precursor to the cinema in Japan. The primary difference from the European varieties is that the projectors are light-weight and portable and the projection is done by several people behind screen. Not only do the still images move, but fast changes between slides or special slides with flipping or moving parts can really give the sense of an early version of the motion pictures. The show is usually accompanied by a benshi-like narrator.

Kinoshita Keisuke's Grave at Engakuji

This year, I again took my Yale Summer Session students on a tour of Kamakura. It was hard to schedule this year because of all the bad weather (it seems like the rainy season has not ended despite the weather bureau's declaration), but we started out where we usually do: Engakuji in Kitakamakura. We begin there not only because it is a very nice Zen temple (Rinzai sect), but also because we can honor two of Japan's great directors, Ozu Yasujiro and Kinoshita Keisuke. It's also an opportunity to show students what's involved in doing "ohakamairi" (I always bring Ozu a can or bottle of whiskey, and most students are surprised by that), but it also gives them a chance to get closer to filmmakers they have seen. This year, I showed The End of Summer to the entire class, and about a third wrote about Twenty-Four Eyes

for their midterm report. Some were genuinely eager to visit these graves.

I wrote about this last year, but Kinoshita's grave is right by Ozu's. If you are looking at Ozu's grave, you just have to turn around 180 degrees and you can see it in the corner, next to the water faucet. I always feel sorry for Kinoshita when I visit. Every time I come, there are always flowers or bottles of liquor at Ozu's grave, but nothing at Kinoshita's. Ozu's grave is usually nice and clean, but Kinoshita's is closer to the surrounding shrubbery, and often has dead leaves or spider's webs on it. We always bring flowers and clean the grave when we visit.