News and Opinion

Reconsidering the History of Japanese Film Theory

I am pleased to announce the publication of Issue 22 of the Review of Japanese Culture and Society dedicated to the theme, "Decentering Theory: Reconsidering the History of Japanese Film Theory." This is the first publication in a non-Japanese language to consider the rich and varied history of Japanese film theory. It presents both translations of some of the major works and scholarly analyses of those theorists and their historical contributions to film thought. A major theme throughout the issue is the unique problem of how to approach and define film theory in Japan.

Thinkers represented include Nakai Masakazu, Hasumi Shigehiko, Yoshida Kiju, Imamura Taihei, Gonda Yasunosuke, Sato Tadao, Kitada Akihiro, and Nakamura Hideyuki, with works ranging in era from 1914 to 2011. They all focus on questions of the status of cinema and how to approach it, but other topics broached include animation, early cinema, mediation, spectatorship, documentary, meaning, and Ozu Yasujiro. A translation of one of Akutagawa Ryunosuke's "film scripts" is also included (Akutagawa wrote the stories on which Rashomon is based).

Reference Works for Researching Japanese Cinema

With the wonderful cooperation of the East Asian Library at Yale University, I've prepared a research guide for Japanese film studies entitled "Japanese Reference Materials for Studying Japanese Cinema at Yale University" that has just been uploaded to the Library website.

It offers a concise introduction to the print and online reference materials in Japanese available at Yale that are essential for studying cinema. If you or any of your colleagues or students need to find out something about a film or director, this guide will help you know where to look, even if you are not using the Yale Library. It covers dictionaries, encyclopedias, filmographies, books, journals, and online databases. I believe the guide is the first of its kind on the net.

It does not substitute for the book I co-authored with Abé Mark Nornes, Research Guide to Japanese Film Studies, which not only explains reference materials in multiple languages, but introduces archives and other institutions important for researching Japanese film. It, however, is not available online.

The Tohoku Earthquake in Japan

Last week I went to Japan as I often do at the beginning of the spring break at Yale. I pay my taxes, do some research, consult with people about projects at Yale, etc. I was actually meeting Tsuchimoto Motoko, the wife of the great documentarist Tsuchimoto Noriaki, for lunch on Friday, 11 March 2011, at a sobaya on the eighth floor of the Takashimaya department store at Yokohama Station. My wife is putting out DVDs of some of Tsuchimoto's work.

It was at 2:46 pm when the quake hit. One gets used to earthquakes in Japan, so at first we just felt it was just another minor trembler. But the shaking got worse and worse and went on and on. I was in Kyoto when the Kobe earthquake occurred in 1995, and that quake started violently, suddenly, and lasted only about 20 seconds. This started slowly and seemed to go on forever, giving you plenty of time to wonder when the building is finally going to fail. Afterwards I found out that Yokohama experienced shaking of Shindo 5- or 5+, which is pretty serious. Motoko-san and I hid under the table. The department store immediately announced the quake on the PA system and provided warnings. It took too long, but finally the shaking died down and Motoko-san and I left the building via the stairs. There was a huge crowd in front of Yokohama Station as many people had fled the nearby structures.

Koreeda Hirokazu at Yale, Day 1

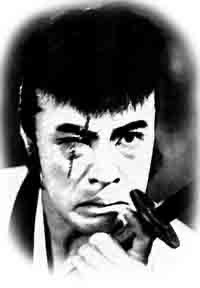

The Japanese filmmaker, Koreeda Hirokazu, director of such award-winning works as Maborosi and Nobody Knows

, came to Yale at the end of February 2011 to show two of his films and conduct workshops with our students. It was a greatly successful event and I want to convey my thanks to him and everyone else who helped make it possible. This is the first of two reports on what he did and said during his stay at Yale.

Although Koreeda arrived on Thursday the 24th (I look him to the famous Louis' Lunch for lunch after he got into town), we put him to work at noon on Friday with a workshop for students who couldn't speak Japanese (one for those who could was held on Saturday). I asked him to prepare a talk and he and I made up a clip reel in the morning. The result was a truly enlightening session.

He showed four clips. The first was from Hitchcock's The Birds: the famous scene of the birds assembling in the playground. Koreeda used this to emphasize that cinema should not be about "why" - for we never learn why the birds attack - but about "how." The second clip was from the end of Fellini's Nights of Cabiria

, where Giulietta Masina turns to the camera and faintly smiles. Koreeda said this was the first time that he really became conscious of the palpable gaze of the director, and of the relationship between the one filming and the one filmed. Next he showed the cafe scene from Kurosawa's Ikiru

, where the young woman shows Watanabe the toy bunny and he finally decides what he must do with the remaining portion of his life, a scene that signifies his metaphorical rebirth. As a young man, Koreeda was as impressed with this film as any other would be, but he began to doubt its humanistic optimism and belief in heros like Watanabe. The result of this doubt can be found in After Life

, which was the fourth clip he showed: the scene where the dead begin introducing themselves, up until an old man is seen being unable to think of a single memory he feels exemplifies his life. That man's name is also Watanabe, and he is Koreeda's answer to Kurosawa: a much more realistic figure of a man who did nothing special in his life and has little to say for it. A non-hero who interested Koreeda much more. The four clips worked together quite well.