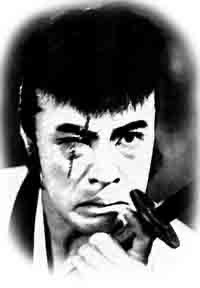

The Japanese filmmaker, Koreeda Hirokazu, director of such award-winning works as Maborosi and Nobody Knows

, came to Yale at the end of February 2011 to show two of his films and conduct workshops with our students. It was a greatly successful event and I want to convey my thanks to him and everyone else who helped make it possible. This is the first of two reports on what he did and said during his stay at Yale.

Although Koreeda arrived on Thursday the 24th (I look him to the famous Louis' Lunch for lunch after he got into town), we put him to work at noon on Friday with a workshop for students who couldn't speak Japanese (one for those who could was held on Saturday). I asked him to prepare a talk and he and I made up a clip reel in the morning. The result was a truly enlightening session.

He showed four clips. The first was from Hitchcock's The Birds: the famous scene of the birds assembling in the playground. Koreeda used this to emphasize that cinema should not be about "why" - for we never learn why the birds attack - but about "how." The second clip was from the end of Fellini's Nights of Cabiria

, where Giulietta Masina turns to the camera and faintly smiles. Koreeda said this was the first time that he really became conscious of the palpable gaze of the director, and of the relationship between the one filming and the one filmed. Next he showed the cafe scene from Kurosawa's Ikiru

, where the young woman shows Watanabe the toy bunny and he finally decides what he must do with the remaining portion of his life, a scene that signifies his metaphorical rebirth. As a young man, Koreeda was as impressed with this film as any other would be, but he began to doubt its humanistic optimism and belief in heros like Watanabe. The result of this doubt can be found in After Life

, which was the fourth clip he showed: the scene where the dead begin introducing themselves, up until an old man is seen being unable to think of a single memory he feels exemplifies his life. That man's name is also Watanabe, and he is Koreeda's answer to Kurosawa: a much more realistic figure of a man who did nothing special in his life and has little to say for it. A non-hero who interested Koreeda much more. The four clips worked together quite well.

To end the workshop, two of my students showed Koreeda their film, a quite ambitious work with some connections with Japan, and he commented on it. The comments were not only precise and helpful - he certainly has a great eye - but they revealed much about his view of cinema. He really stressed that every shot should have a reason, and complained of contemporary films in both Japan and Hollywood which seemed to just multiply shots in order to prevent the audience from getting bored. This could sound like Koreeda is a classical director, but in the next day's workshop, he stressed the "reason" need not be narrative, but can be aesthetic or ethical (this brings Koreeda closer to the realm of art cinema). Establishing such reasons should prompt the filmmaker to create a more economical style centered on "key shots" that reduce the number of shots in a scene (he thus pointed to specific shots or cuts which he felt were unnecessary). I felt I had experienced a very concrete lesson in filmmaking.

After a nice reception, we showed Koreeda's 1996 television documentary Without Memory, which is about a man named Hiroshi who has largely lost the ability to accumulate new memories (called Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome) because he was denied vitamins during a long hospital stay, the result of unreasonable rules regarding insurance at the time. The theme of memory is obviously central to Koreeda's oeuvre, and in the Q & A after the screening, Koreeda stressed how Without Memory relates to After Life. In both works, the centrality of memory to personal identity is amended with the proviso that the memories that define oneself need not be one's own; "one's memories" can include the memories others have of you. He said that at the time he made Without Memory - when he was still just a director at TV Man Union - he was wondering what it meant to be a "shuzaisha" or reporter/director/investigator. He saw Hiroshi as a kind of shuzaisha - someone who must get information from others - and took encouragement in the possibility that he himself (Koreeda) could also live on in the memories of others. (This, of course, could connect with the use of film in After Life.)

Koreeda talked a lot about the importance of documentary in his work. In some ways, it defines the basic stance in all of his filmmaking. He in particular emphasized that he considered the fundamental ethical standpoint of documentary to be filming from the standpoint that one does not - or cannot - know the person one is filming. Not only much fiction filmmaking, but also much documentary, begins from the presumption that it knows the people in the event or the drama. That, to Koreeda, is unethical, and therefore even in his fiction films he avoids subjective cinematic structures that offer easy access to the internal states of his characters. This is again the focus on the "how," not the "why."

This aligns him with the major trend in Japanese film of the 1990s, as I argue in my book on Kitano Takeshi, but Koreeda repeatedly throughout the visit tried to distance himself from many of those filmmakers. If many of them, from Kurosawa Kiyoshi to Aoyama Shinji, were educated under Hasumi Shigehiko and took up a somewhat cinephilic approach to film, Koreeda stressed that while others may make films on the basis of what they see in other films, he makes films on the basis of what he sees apart from films. I think this is crucial to how he defines himself (as well as defends himself, since some of the Hasumi-influenced film critics have been very critical of Koreeda in Japan). That said, he was quick to stress the importance of film viewing in his education and particularly cited Hou Hsiao-Hsien

, Ken Loach, Victor Erice

, John Cassavetes

, and Lee Chang-dong as directors whom he sees as important, if not necessarily influences. Among Japanese filmmakers, he likes Naruse Mikio

the best.

Stay tuned for the report on Day 2.