News and Opinion

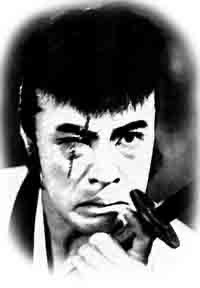

Kojiro

This is not film news per se, but rather a memorial in virtual space for a departed loved one.

Yesterday evening, April 27, our tabby cat, Kojiro, was killed by a speeding car just two houses away from us. It was quite a shock, in part because our life with this mysterious cat was quite short-lived. He just showed up on our doorstop one rainy November night last year, and kept coming back until it seemed he had chosen us for his new family. He stayed indoors for most of the winter, but come spring, he would run outside and sometimes not come back at night. He wasn't the most attractive cat, yet he was very friendly - but he rarely ever purred. A very contradictory creature who was quite an individual. Only a bit over a year old, he left us all too suddenly.

Kojiro came to us like a wandering samurai, so we named him after Sasaki Kojiro, Miyamoto Musashi's legenday opponent popularized in the Yoshikawa novels and in various movies, and played by such cool dudes as Tsuruta Koji and Takakura Ken. (Our cat just did not seem someone we could name Musashi.) There's even an eponymous 1967 Inagaki Hiroshi film on this rather tragic figure starring Onoe Kikunosuke. I wonder whether we shouldn't have given him a more propitious name, although we more often called him by his nicknames Obojo and Obo.

The Culture of Japanese Fascism

The other day I received my copy of The Culture of Japanese Fascism, a long-awaited anthology edited by Alan Tansman in which I have an article. "Long-awaited" is one way of putting it: the book is based on a conference actually held at Berkeley back in 2001. It probably took that long getting everyone together, but it was well worth the wait. The book not only presents the cultural dimension of Japanese interwar fascism, one that has not been fully explored, but it does it from a variety of perspectives that do not simply assume a universal "fascism" and find examples of that in Japan, but attempt to understand the particular manifestations of state and nationalist power in Japanese culture. My essay, "Narrating the Nation-ality of a Cinema," for instance, complicates the easy ascription of the term "fascist" to prewar film if one defines fascism, in part, as a form of ultra-nationalism. I argue that the process of Japanese cinema assuming "nation-ality" (the state of being national) was in fact complicated by problems in the film industry and the colonial situation, and was not "already the case" by the start of the period of total mobilization. In the end, I argue that fascism in cinema is less the representation in cinema of the state of ultra-nationalism than the process of forcing nation-ality on a cinema and its audiences that are never already national.

Yoshida Kiju and Okada Mariko

I was invited up to Boston last week to participate in a panel discussion with Yoshida Kiju and his wife Okada Mariko held in conjunction with the Yoshida retro at the Harvard Film Archive. Haden Guest, the head of the Archive, was the chair, with the other panelists being me, Markus Nornes and Roland Domenig. The idea was to have an occasion apart from the usual post-screening Q & A session (where few follow-up questions are allowed), during which we could really pursue some issues in depth. To aid in the endeavor, it was made a small event with a very small audience. This was my second time doing an event with Yoshida-san, the first being the Yoshida Kiju Symposium at Meiji Gakuin some years past.

One hope was to focus more on Okada-san, who unfortunately does not get as many questions in the usual Q & A session as she deserves. She proved quite talkative and her stories ended up taking up nearly half of an event that, going overtime, totalled nearly two hours. One got a strong impression of an actress passionately dedicated to her craft. I asked her about something Yoshida once wrote about the need for actors to be more free, and to exceed the roles given them by the film or director through their bodily presence, but while she voiced her preference for working with a director who thinks that way, she also presented herself as a performer who is well able to negotiate different directorial styles, from the freedom Yoshida provides, to the precise bodily direction Ozu imposed. Okada was most passionate when I, following up on a Markus question, asked her about young idol or tarento performers. While respecting that that they do what they are supposed to do - play themselves, not any character beyond themselves - she strongly voiced her opinion that such performers are by definition not actors.

Richie on A Page of Madness

Donald Richie again honored me by being the first to review my book on Kinugasa Teinosuke's A Page of Madness, penning one for the Japan Times this last weekend. He was also the first to write a review of my book on Kitano Takeshi as well. What was particularly gracious of him this time was not just the favorable review, but that he wrote such nice comments even though I criticize him in the book. I actually used something he wrote early on about A Page of Madness as an example of the almost mythical narrative about the film's creation that does not really accord with the facts, commenting on how that narrative of independent, avant-garde creation has been so powerful, it has seduced even the best of film scholars. Well, Richie has been the best of persons as well, writing a very fair review even despite that use of his writings.

Speaking of Richie, I was interviewed on camera a couple of months ago for a documentary being made about Donald Richie. It should be an interesting work. Also, next month will see Donald being honored by the Society for Cinema and Media Studies conference in Tokyo. Donald has been somewhat of a presence in my year so far.

The Benshi's New Face (From Old)

I've been meaning for sometime to add some of my old articles to the site, but have not gotten around to it (sorry!). But I was searching around on the internet for something else and found that one of my first published articles is available online. I have added it to the Internet Articles section.

The piece is called "The Benshi's New Face: Defining Cinema in Taisho Japan" and it was published in 1994, when I was still a doctoral student. It considers how discourses attempting to define cinematic institutions such as the benshi served not only to articulate the medium, but also to enmesh cinematic practices in the operations of power. It is a foundational article for the thinking that leads up to my book on early Japanese film culture, but it was published in journal with limited circulation, so it is not well known. Iconics is the international edition of the journal of the Nihon Eizo Gakkai (Japan Society of Image Arts and Sciences), the main academic society in Japan that includes the study of cinema. I was later editor of that journal, as well as a managing director (jonin riji) of the JASIAS.

Adopting Hayashi Chojiro

This news has been out for a couple months, but I thought I should mention the most recent feat by the Film Preservation Society (Eiga Hozon Kyokai) in Japan: preservation work on a digest version of the 1929 silent film Sukeroku of the Black Hand Gang (Kurotegumi Sukeroku). You can see an English article here.

The Film Preservation Society is actually a non-profit organization (NPO) composed of mostly everyday volunteers who are interested in preserving the celluloid heritage. Beyond showing films and spreading awareness and knowledge about preservation, their most famous undertaking is the Film Adoption (Eiga no Satooya) project, which looks for individuals to fund the rescue of films that have not gotten attention so far. In a sense, it is aligned with the orphan film movement in that it is trying to save works that are outside the commercial mainstream or which have been abandoned because of their lack of commercial potential, but at least in this case, Sukeroku of the Black Hand Gang has an owner and the film is, as I will note below, not uncommercial. One of the Society's previous successes was the restoration of Saito Torajiro's masterful comedy short Modern Horror: 100000000 Yen (Modan kaidan 100000000-en, 1929). Given that not all efforts have been made to preserve the film heritage in Japan (a problem Markus Nornes and I touch on in our upcoming guide to film archives, libraries and research resources), these volunteer efforts are important.