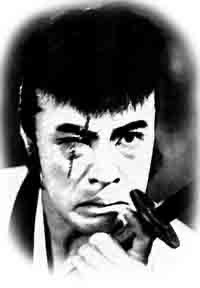

I was invited up to Boston last week to participate in a panel discussion with Yoshida Kiju and his wife Okada Mariko held in conjunction with the Yoshida retro at the Harvard Film Archive. Haden Guest, the head of the Archive, was the chair, with the other panelists being me, Markus Nornes and Roland Domenig. The idea was to have an occasion apart from the usual post-screening Q & A session (where few follow-up questions are allowed), during which we could really pursue some issues in depth. To aid in the endeavor, it was made a small event with a very small audience. This was my second time doing an event with Yoshida-san, the first being the Yoshida Kiju Symposium at Meiji Gakuin some years past.

One hope was to focus more on Okada-san, who unfortunately does not get as many questions in the usual Q & A session as she deserves. She proved quite talkative and her stories ended up taking up nearly half of an event that, going overtime, totalled nearly two hours. One got a strong impression of an actress passionately dedicated to her craft. I asked her about something Yoshida once wrote about the need for actors to be more free, and to exceed the roles given them by the film or director through their bodily presence, but while she voiced her preference for working with a director who thinks that way, she also presented herself as a performer who is well able to negotiate different directorial styles, from the freedom Yoshida provides, to the precise bodily direction Ozu imposed. Okada was most passionate when I, following up on a Markus question, asked her about young idol or tarento performers. While respecting that that they do what they are supposed to do - play themselves, not any character beyond themselves - she strongly voiced her opinion that such performers are by definition not actors.

The content of Yoshida-san's discussion perhaps did not seem too new to those who have heard him talk before or read his books. He again emphasized his belief in the inherent ambiguity or otherness of the image, in a form of human perception (the anarchy of sight) that precedes knowledge or categorization, or in an approach to authorship that refuses to "own" the film. It again reminded me of the parallels between Yoshida and contemporary filmmakers like Aoyama Shinji or Kurosawa Kiyoshi, ones which are not likely defined by a narrative of influence (Aoyama in fact discovered Yoshida after he wrote his manifestoes on a new New Wave centered on treating the image as an other).

What was interesting was the reaction - Markus called it "visceral" - to Roland's question about landscape theory (fukeiron). Yoshida was well aware of the concept - most famously developed by Matsuda Masao in the late 1960s - but intriguingly "misread" it as encouraging narrative more than it really does. This probably signals his strong aversion to the concept, one that, especially when combined with his voiced belief that the 1960s left was supported more by emotion than thought, and thus suffered mass withdrawals whenever death became a real possibility, reflects his complex relation to the New Left.

Afterwards, we had a nice dinner at the Faculty Club where the couple regaled us with tales of their marriage ceremony in Germany in 1964, of Kido Shiro, etc. Okada-san has just finished penning an autobiography, which should appear in Japanese this fall.

Thanks to everyone for the insightful discussion. I look forward to grilling Yoshida-san some more for the film theory book I am writing.