News and Opinion

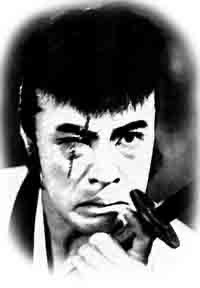

Kimura Takeo

The Asahi reports this morning that the illustrious art director, Kimura Takeo, passed away on March 21, 2010, of pneumonia. He was 91.

Kimura is most famous for his collaborations with Suzuki Seijun, but KImura had already worked in the industry for over 20 years before he first joined Seijun on Akutaro in 1963. Kimura entered the Nikkatsu Tamagawa studio in 1941, but debuted as an art director at Daiei (which took over Nikkatsu's production division during the big wartime mergers) in 1945. His first well-known works were literary adaptations such as Gan (1953) or family dramas such as Keisatsu nikki (Police Diary, 1955). He returned to Nikkatsu when it resumed production in 1954. He was central in helping create the "mukokuseki" or "nationless" feel of Nikkatsu Action films, creating a unique world mixing the imaginary and the real, foregrounding style and color. That in some ways culminated in his work on Seijun's Tokyo Drifter

(1966).

That was not his only style, however, as he also worked on the social realist films of Kumai Kei such as Shinobugawa (1972) and Umi to dokuyaku (Sea and Poison, 1986). His most famous work was probably Seijun's Zigeunerweisen (1980), but other well known films include Itami Juzo's Tampopo

(1985). He won a prize at the 1990 Montreal Film Festival for his work on Shikibu monogatari. As a footnote, Kimura was one of the eight people (including Sone Chusei, Yamatoya Atsushi, etc.) who participated in the scriptwriting for Seijun's films at Nikkatsu under the name Guru Hachiro.

Kimura returned to the news in the last few years for taking up the megaphone, helming the short Mugen Sasurai in 2004 and the feature films Yume no mani mani (2008) and Ogonka (2009), making him one of the oldest "new directors."

Kimura won many awards during his long career involving over 230 films. He won the Yamaji Fumiko Culture Award in 1991, and the Mainichi Art Award in 2006. He also served as the head of the Nikkatsu Visual Arts Academy. He wrote a number of books about his career and art directing, including Waga honseki wa eigakan (1986), Eiga bijutsu (2004), and the recent Urabanashi hitotsu eiga jinsei kyujunen (2009).

He was arguably the original and prominent of Japanese art directors (though note my post about Muraki Yoshiro) and he will be missed.

Osu in Nagoya

Last weekend I made a brief trip to Nagoya to attend a workshop headed by Fujiki Hideaki of Nagoya University. It was a preparatory workshop for one of the upcoming volumes in Shinwasha's Nihon eigashi sosho series, which will focus on audiences. I talked about the issue of theory in the history of Japanese film criticism. All the papers were interesting and this looks like it will be a great volume. (Update: And here it is.)

Even though this was only my third of fourth time in Nagoya, Nagoya holds a special place in my heart since it placed a significant role on the history of Kinugasa Teinosuke's A Page of Madness, and thus appears a lot in my book on the film. In what Makino Mamoru calls "Nagoya modernism," film fans in Nagoya not only wrote a lot about that film in dojinshi such as Chukyo kinema (one example of which I translated in my book), but arranged for special screenings in the city.

With that knowledge in mind - and my general interest in movie theater districts - I decided to spend some of my extra time by going to Osu, which used to be the main place to see movies in prewar and immediate postwar Nagoya, a time when there were over a dozen cinemas in the district. Centered on a Kannon temple, Osu resembled Asakusa in certain ways, with a pleasure quarters nearby, lots of entertainment venues, and a plebeian culture (here are some photos of remnants of that atmosphere). Osu also somewhat suffered the fate of Asakusa, which in the postwar lost its place as the entertainment center of Tokyo (if not of Japan) to more upscale neighborhoods like Ginza, Shinjuku and Shibuya. But unlike Asakusa, which still has a number of movie theaters in the Rokku district, there are none left in Osu. I was hoping I could find some small traces of those theaters (like one or two converted into other businesses) like I did in Kyoto's Shinkyogoku, but if there were any, I missed them. (Chitose Gekijo, which was one place where A Page of Madness played, was a little bit north of Osu in Hirokoji, but I didn't have time to go there.) The only trace of that old entertainment center is the Osu Engeijo, which still programs rakugo and other traditional vaudeville.

Studying Film in Japan

I often get mail from students who are hoping to study film in Japan (I have an old, somewhat out-of-date post about studying Japanese film in North America). There are a variety of opportunities, but they can be divided according to whether you want to do film studies or filmmaking.

Film Studies:

One of the sad facts about Japanese film culture is that Japan does not value that culture much. There is little government support for film culture and education (except when it can immediately turn a profit or build some box as a payoff to construction industry friends), and universities have long ignored film studies as a discipline. The ignorance the average Japanese has of his or her own film culture can be appalling at times. But there have been a few universities that have valiantly pursued film studies and sport excellent scholars. Some have very good libraries (which you can learn more about in our Research Guide to Japanese Film Studies). I definitely recommend that anyone seriously studying Japanese film spend at least a year in Japan partially associated with a university. It is a great way to meet scholars and students, attend some special classes, and gain access to university collections. The value of doing a degree in Japan, however, is debatable. It could possibly help your resume to add a masters from a Japanese institution to a PhD from a North American university, but frankly PhDs in film studies from Japanese universities have a very hard time finding a job in Japan, let alone elsewhere. The job situation may be different outside North America or the English-speaking world, so you should get a lot of advice from knowledgeable academic advisors before taking the plunge. The sad fact, however, is that Japanese institutions as a whole are not highly regarded world-wide. This is unfortunate because there are a number of Japanese scholars who are doing some of the best work on film in the world; ignoring that is often just part of Eurocentrism. Yet the current institutional fact is North American institutions are just better funded and managed. It is still advisable to attend a PhD in North American program like the one at Yale, and spend a year or two in Japan as part of the program.