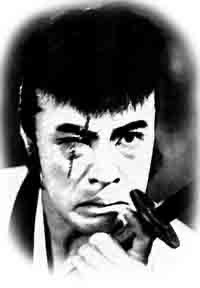

I was very sad to see that the film scholar Hatano Tetsuro (波多野哲朗) passed away on October 2, 2020, at the age of 84. Hatano-sensei was an important figure in post-1960s film studies in Japan. He was one of the editors of the very influential journal Shinema 69 (later Shinema 70, etc.), which set the tone for film criticism of the 1980s and 1990s, especially under the leadership of Hasumi Shigehiko. Hatano was a core member of the team that created Gendai Nihon eigaron taikei (Systems of Contemporary Japanese Film Thought, 1970-72), still the best collection of postwar film criticism and theory. Later, he teamed with Iwamoto Kenji (my co-editor on the prewar theory anthology) to produce Eiga riron shusei (Theories of Film: An Anthology, 1982), an important anthology of foreign and Japanese film theory. Hatano's other books include Eiga kantoku ni naru ni wa (How to Become a Film Director, 1993) and translations of works such as Sheldon Renan’s An Introduction to Underground Film, and Jon Halliday’s interviews with Pasolini. He was also a filmmaker and a motorbike aficionado, most known for shooting his 16,000 kilometer motorcycle trek across Eurasia. His documentary, Salsa and Chanpuru: Cuba/Okinawa, was in his words a “musical documentary” about Okinawans who emigrated to Cuba, and was released in theaters in 2008. He taught for over thirty years at Tokyo Zokei University, starting as an adjunct in 1968 and ending as an emeritus professor. He also taught at Nihon University after retiring from Tokyo Zokei.

I knew Hatano-sensei through the Japan Society of Image Arts and Sciences, for which he served as president. He was always the kind gentleman, but one with the most pointed questions. He was also honorary advisor to the Japan Society for Cinema Studies.

I was most indebted to Hatano-sensei for his help when I was writing my history of Japanese film criticism (available here). His commentaries published in the Gendai Nihon eigaron taikei were already brilliant, proving such incisive concepts as the “aristocracy of sensibility” to describe impressionist film criticism in Japan. But he also met with me to talk about his perspective on a long history he himself was involved in, noting in particular the lack of “thought” (or theory) in the development of Japanese film criticism. My history was first published in Japanese (in Kankyaku e no apurochi), and it meant so much to me when Hatano offered his praise for my analysis.

I hope he rests in peace. ご冥福をお祈りいたします。