Kurosawa Kiyoshi has long been one of my favorite filmmakers, but one I’ve found very hard to talk about. Perhaps that difficulty is one reason I like him so much: his films resist our ability to comfortably confine them in words, and challenge our systems of knowledge and perception. That’s one reason they are so attractive but also so frightening.

That’s also why I have always been at somewhat of a loss when I encounter articles on Kurosawa that profess to know him or his works through some allegorical, postmodern, or ecocritical methodology. There’s a lot we can learn about Kurosawa from such articles, but it still stikes me that many of them were less watching his films in their complexity than imposing their interpretations. And given that Kurosawa’s films are populated with detectives and detective-like figures whose interpretations are problematic, that approach can be self-defeating, if not blind to what’s going on in the films. They effectively offer comfort against a set of films that are fundamentally disturbing.

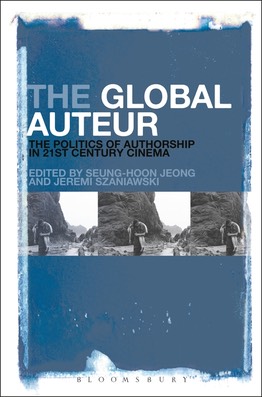

I have written about Kurosawa before, including a short piece in John Berra’s Directory of World Cinema: Japan 2, and a longer piece on repetition in recent Japanese horror films in Minikomi (which you can now download on my Yale BePress site). When I got an invitation from two former Yale PhD students, Seung-hoon Jeong and Jeremi Szaniawski, to participate in an anthology they were preparing on twenty-first century auteurs, I consented to write about Kurosawa, but with some trepidation. As the two of them unfortunately found out, it was a bit scary for me to write this piece.

It helped to run into an article that Shinozaki Makoto—later the director of Okaeri and Sharing—wrote in the early nineties in which he called Kurosawa not only a trickster or swindler (peten-shi), but also a missionary (dendoshi)—this long before Kurosawa called Mamiya in Cure a dendoshi. That put a word onto Kurosawa and his cinema, but one that recognized how he both celebrates cinema while hinting that it is unknowable even to him. These words also aligned Kurosawa with the “monster” in one of the best horror films of all time.

In the end, I tried to consider Kurosawa Kiyoshi as a ghostly auteur, a different trickster behind the cinema who plays the doubleness of ambiguity against the singularity of meaning. He provides us with insight in how to negotiate media ecology during the supposed end of cinema and the birth of the digital age in Japan, especially against the background of Japan’s place as a nation in a globalized world. Kurosawa, I argue, uses the ghostliness of cinema to explore an ethics of looking, a reparative gaze that negotiates a space in the current geography of media and nations. Here’s the citation:

- Aaron Gerow. “Kurosawa Kiyoshi, Dis/continuity, and the Ghostly Ethics of Meaning and Authorship.” The Global Auteur: The Politics of Authorship in 21st Century Cinema. Eds. Seung-hoon Jeong and Jeremi Szaniawski. New York: Bloomsbury, 2016. Pp. 343–359. ISBN 978-1501312625

The rest of the anthology is quite impressive, with contributions from illustrious scholars such as Fred Jameson, Thomas Elsaesser, and Dudley Andrew, as well as other Yale grads like Michael Cramer and Victor Fan. Unfortunately, there’s no paperback edition yet, but you can get it from Powells, Amazon, or from Bloomsbury.