Even though

I once worked for the YIDFF, this year’s festival was my first since 2009, so

my first impression one of nostalgia. Seeing the same old places, meeting old

friends, drinking at Komian, basking in the intellectual atmosphere of the

festival. This year’s festival had many great moments, but I also felt the

YIDFF also needs to look back a bit more at the past.

Even though

I once worked for the YIDFF, this year’s festival was my first since 2009, so

my first impression one of nostalgia. Seeing the same old places, meeting old

friends, drinking at Komian, basking in the intellectual atmosphere of the

festival. This year’s festival had many great moments, but I also felt the

YIDFF also needs to look back a bit more at the past.

I had some obligations, especially helping my wife a little at the Daily Bulletin (I penned a short piece for them looking back on its history, since I worked there during the 1993 festival). So I couldn’t see everything I wanted to. I saw a few non-Japanese films, and was particularly impressed with John Gianvito’s Wake (Subic) (which shows some significant influence from Tsuchimoto Noriaki’s work) and Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro, but I focused mostly on Japanese films. Unfortunately, there weren’t many that thrilled me.

Possibly the most interesting were Yamashiro Chikako’s works, The Beginning of Creation/A Child and A Woman of the Butcher Shop, which were showing in New Asian Currents (which I programmed back in 1995). Both were originally installation pieces and would be hard to call documentary under a traditional definition (Yamashiro-san told me this was in fact the first time her works had been shown in a movie theater). The first was a record of Kawaguchi Takeo’s effort to literally draw out and emulate Ohno Kazuo’s dance; the second a more narrative exposition of gender and occupation in Okinawa (I have to keep this in mind if I ever update my article on representations of Okinawa). While both exhibit a strong, and often political concern for the body, if not also a desire to return to origins (the sea, the same cave in both), the two are also very aware of mediation, to the point of thinking about the materiality of digital video.

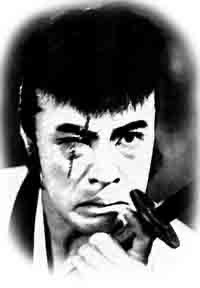

The “must-see” for fans of Japanese documentary was Hara Kazuo’s first film in a long time, Sennan Asbestos Disaster, which showed in the International Competition. It was certainly well-done and has gone on to win awards both at Yamagata and Busan. But this document of the efforts by victims of asbestos poisoning to sue for state compensation differs from Hara’s previous works in a number of ways: the focus is on a group, not an individual; Hara rarely battles with his subjects (he refrains from critiquing their actions); and the film has a happy ending. You can still see, even in the opening credits, Hara’s efforts to bolster the energy level. Yet even Hara complained in the Daily Bulletin that the film lacked the sharp or rebellious (tongatta) individual you find in Okuzaki Kenzo or Inoue Mitsuharu. The last half of the 3.5 hour film is very conscious of this, and shows Hara’s failed attempt to get one of the activists, Yuoka, to act as his provocateur. As I told Hara-san, as both a compliment and a critique, this film is a film about his failure to make the film he wanted to make.

The other Japanese film in the Competition was Tremorings of Hope by Agatsuma Kazuki. This was one of several 3.11-related documentaries at the YIDFF. Agatsuma comes out of ethnography and this film is actual a sequel to his The People Living in Hadenya, which was started as an effort to record the lives and customs of the people of a small seaside town in Miyagi, but changed with the quake and tsunami disaster. Tremorings focuses on the post-3.11 efforts to maintain the village community, centered on reviving the yearly lion dance. Given his long association with the community, Agatsuma gets as close as one could expect of any outsider, emotionally presenting the deep personal conflicts of the individuals. But Agatsuma does not really confront or critique them. In fact, one cannot help but think he is projecting his ethnographic desires—that the lion dance has to be essential to this village—onto his subjects.

One thing that was apparent with the 3.11 documentaries I saw is that few of these younger filmmakers have learned from the history of documentary. Commitment to a subject does not mean refraining from critique. One need not battle with them like Hara, but Tsuchimoto’s respectful detachment, for instance, is still a distance. Even if one is politically committed, as Ogawa Shinsuke was, the commitment should still be deep and thoughtful—and still investigate the subject. It so happens that the closing film, The Power of Expression: The Minamata Producer Speaks by Inoue Minoru and Kataoka Nozomi, was actually about Takagi Ryutaro, the producer of many of Tsuchimoto Noriaki’s and Higashi Yoichi’s films. Some could learn from his history (though in the end, I found the film not only lacking in details but also a bit deflating; it needed a historian or critic to balance Takagi’s occasionally regretful accounts of what he thinks were failures).

Oura Miran’s The Road Home was a personal documentary about her family, who were forced to evacuate after the Fukushima Daiichi accident. While it presents a different side to the 3.11 narrative, and offers that moment of personal/family crisis that can render a personal documentary dramatic, it interrogates neither the politics of the personal or this form of documentary. When I asked her about why she chose this form and how she relates to the history of Japanese personal documentary, going back to Suzuki Shiroyasu and Hara Kazuo, she could only say it was her professor who suggested she shoot it this way. (It does seem the film also benefited from the Rough Cut section of YIDFF 2015, where it received a lot of advice.)

Tashiro Yoko’s On to the Next Step: Lives after 3.11 was a three-hour account of three families vaguely united by post-3.11 anxiety and worries about plans to build a new nuclear power plant in Aomori. But that’s about it. There’s no real discussion of why these three were chosen (at least two of whom are involved in organic food production, and thus may reflect a certain conscious choice), nor any interrogation of their actions or positions.

In the end, the most interesting Japanese works that I saw were experimental. Beyond Yamashiro’s works, there was Hori Teiichi’s Tenryu-ku Okuryoke Osawa: Bessho Tea Factory, which offered one example of minimal documentary: while presenting the harvest and preparation of green tea leaves, it offers absolutely no explanation of what is going on, making this a film that demands the viewer work not only to understand the process, but also notice other cinematic motifs and repetitions. (Hori unfortunately died in July at age 47 during a retro of his works at Porepore Higashi Nakano.) Between Yesterday & Tomorrow: Omnibus 2011/2016 is a project headed by Maeda Shinjiro, who after 3.11 asked a number of experimental filmmakers to make 5-minute works following a set of rules: on day one you record your voice talking about what you will film; on day, you film; and on day three, you talk about what you filmed. You can edit it after that, but you can’t change the sound. At YIDFF, they showed two works each by Oki Hiroyuki (whom I interviewed a long time ago), Suzuki Hikaru, Ikeda Yasunori, and Takashi Toshiko, made five years apart. This was an interesting experiment investigating time and the relation of sound and image, especially temporally. The return to the project in 2016 added yet another productive dimension of time to the project. Finally, there was a screening of two of Shichiri Kei’s films: Dubhouse: Experience in Material No.52 and Another Side / Salome’s Daughter-Remix. The first is an intriguing investigation of materiality in film, not simply through exploring cinema's ability to present physical space (a house) through changing light, but also foregrounding the grain of 35mm, to the point we start seeing things in the grain that are there but not there. The second is Shichiri’s attempt to work through the potential of digital—especially the concept of the remix—in film and performance, with the multi-layered film presented itself being just one version of a series of versions of the same footage.

Perhaps I found these more interesting because these were aware of and were investigating their medium. That was not the case with the work of other young documentarists. It made me regret that the YIDFF has not organized a retrospective of Japanese documentary works since the 2011 series on television documentary. Perhaps it could be a mixture of Japanese and foreign works, but the YIDFF should take the lead in educating young filmmakers about the history of their medium and the issues they will face. A retrospective on personal documentary, for instance, is long overdue.