In coming to Japan for this year of research, I was eagerly expecting my first attendance at the Yamagata, Tokyo, and Filmex film festivals in eight years, even if I knew their plusses and minuses. But I was also very pleased to go to a festival that I learned about for the first time: the Nichigei Film Festival, which took place in December.

“Nichigei” stands for the Nihon Daigaku Geijutsu Gakubu, or Nihon University College of Art. The study of film at Nichidai goes back to at least 1929 and has been one of the core courses of the College of Art since it was formed in 1949. The focus has been on production, with such graduates as Ishii Gakuryū, Matsuoka Jōji, Kanai Katsu, and Adachi Masao, although there are also students researching film history. Faculty have included Ushihara Kiyohiko and Tanaka Jun’ichirō.

One of the current professors is Koga Futoshi, who has had a long career starting at the Japan Foundation and continuing with the Asahi Shinbun newspaper. At both, he organized a large number of film events and festivals. He still writes a lot on film (check out his blog) and was a member of the Asahi ratings panel with me at the TIFF. After becoming a professor at Nichigei, Koga has taught a variety of courses, but quite interestingly one for third year students is about film programming. As the main assignment for the course, students have to plan and put on a film festival of their own that will show at a regular commercial theater. This is the Nichigei Film Festival. They start by having each student put together a serious proposal for a festival, from which the best are selected and presented to Eurospace, an art theater in Shibuya, which then selects the one to put on. The students then have to arrange for renting the films, creating a catalog, arranging for advertising, and inviting guests. They then have to run the week-long festival once it starts.

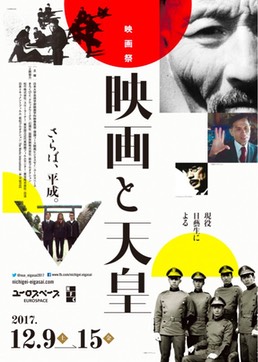

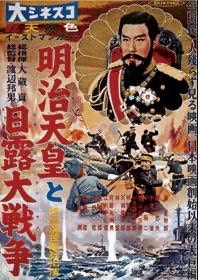

This year’s festival, the seventh one, was on a challenging topic: “Cinema and the Emperor.” Not only is the emperor of Japan himself a delicate topic, given how there are still right-wingers who will threaten and even assault those whom they see as offending the emperor, but given that the existence of the modern emperor has revolved around his media representation, presentations in film have had a complicated history. Before 1945, the official photographic portrait of the emperor, or goshin’ei, had to be treated very carefully, but if you look at some of the early films of the imperial family, such as the documentary of the Crown Prince Hirohito’s visit to the Moving Picture Exhibition in 1921, which was also shown at the festival, you could see very high angle shots of the sacred body that would not be allowed later. The film The Sun (Nichirin) ran into problems with authorities in 1925 for presenting the emperor’s ancestors in a fiction film. After WWII, you finally see actors playing emperors, with Arashi Kanjurō most famously playing the Meiji Emperor in a series of successful Shintoho films in the late 1950s. Representations have changed over time, yet there were still fears of right-wing protests when Alexandr Sokurov’s The Sun, about Hirohito in the last days of WWII, showed in Japan in 2006 (I wrote an essay for a Japanese anthology on that film).

So most everyone I know who heard about the Nichigei theme expressed surprise and concern. Perhaps it is the strength of the young, who don’t have the worries of us older folks, but Koga’s students went ahead with it anyway (thanks of course to Eurospace) with no major problems. It was quite successful.

The festival program featured many kinds of films from different eras, including documentaries ranging from Kamei Fumio’s The Japanese Tragedy to Hara Kazuo’s The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On, and fiction films ranging from Abe Yutaka’s Japan Undefeated to Oshima Nagisa’s Sing a Song of Sex and Okamoto Kihachi’s The Longest Day.

What most interested me was a rare screening of The Solitary One (Kodoku no hito / 孤独の人), a film directed by Nishikawa Katsumi for Nikkatsu in 1957, and starring Tsugawa Masahiko, Kobayashi Akira, and Tsukioka Yumeji. The film is an adaptation of Fujishima Daisuke’s novel based on his own experiences at the elite Gakushūin High School, then mostly attended by scions of big business and former aristocrats, where he was classmates with Crown Prince Akihito (now the Heisei Emperor). It has never come out on VHS or DVD and is almost never shown, so this was a truly unique occasion.

The Crown Prince is a character in the film, but in a sign of the studio treading carefully about the topic of representing the imperial family, his face is never shown. Obviously an actor is playing him, but we only see his feet, his hands, the back of his head, or his body in an extreme long shot where is face is indiscernible. In some cases, we only see metonyms of him, such as his gloves, or hear his voice off-screen. But he is in many ways the main character, since he is the solitary one of the title.

In terms of genre, the film is a youth film (seishun eiga), which was one of Nikkatsu’s staples. Even as it established its own genre of Nikkatsu Action in the late-1950s, it continued to make youth films, many starring Yoshinaga Sayuri, that were very successful. The Solitary One has many moments typical of the category. It is set at an all-male school, but the characters' camaraderie is central to the film. The boys energetically act out of pure feelings of friendship and have a good male cry when things don’t work out. They have lovers—Tsugawa is involved with an older woman and Kobayashi with a girl his age—and have the conflicts with family and others that young love generates.

What makes this a youth film in the end, however, is the Crown Prince. This is a youth film that not only defines youth, but also justifies the youth film genre and its vision of life, through negation. Youth is specifically what the Crown Prince cannot experience. That is the central of several narratives in the film. Time and time again, his friends try to arrange typically youthful experiences for their friend, but they are blocked by the Imperial Household Agency and other authorities. This culminates in the incident (based in real life) in which a couple of friends took the Prince to the Ginza without permission, where he walked and drank tea unannounced with regular people, only to be essentially told that it will never happen again. The tears his friends shed are not only for the Crown Prince, but for the glories of youth that always pass—but will always return in the form of a Nikkatsu youth film. The Imperial family, which at that time was being reshaped in the media into a typical bourgeois family, is here shown in good postwar democratic fashion as deserving of that bourgeois life, but blocked from it by remnants of prewar emperor worship (represented by the Kyoto inn, for instance, building a new wing just for the Prince’s visit and pleading he stay there apart from his friends). Effectively, it connects youth film sympathy for the human Crown Prince with democratization, rendering the Imperial family not an obstacle to but a standard for acheiving democracy. The Solitary One is a fascinating example of cinema’s relation not just to the emperor, but also to postwar democracy.

Film programming is to me an essential aspect of not just film culture but film study. Koga’s class is an example that should be emulated elsewhere (perhaps at Yale?). Given the great job they did in 2017, I wish the Nichigei students best for their festival in 2018.