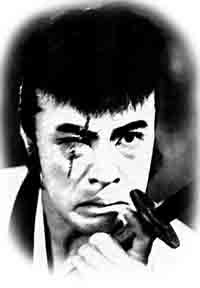

Nagato Hiroyuki

The news sites report that the actor Nagato Hiroyuki passed away on May 21 at the age of 77.

To talk about Nagato is in some ways to talk about the Makino dynasty in Japanese film history. Nagato's grandfather was Makino Shozo, the Kyoto theater manager who "discovered" Onoe Matsunosuke and made him the first big film star in the 1910s. He went off to start his own production company, Makino Productions, and fostered many of the great jidaigeki stars such as Bando Tsumasaburo, Kataoka Chiezo, and Arashi Kanjuro. He also helped up and coming directors such as Kinugasa Teinosuke, the director of Page of Madness. He is widely known as the father of Japanese cinema.

Shozo's son was Makino Masahiro, one of the greatest Japanese film directors (who unfortunately is largely unknown abroad). Shozo's daughter was Makino Teruko, an actress who, after actually having once eloped with Tsukigata Ryunosuke (who played the villain in Kurosawa's Sanshiro Sugata), ended up marrying the actor Sawamura Kunitaro. He is most memorable for playing the bumbling but affable samurai searching for a pot in Yamanaka Sadao's wonderful Tange Sazen and the Pot Worth a Million Ryo. Kunitaro was the brother of Kato Daisuke, a Kurosawa favorite and one of the Seven Samurai

, and of Sawamura Sadako, herself a famous actress.

It was Teruko and Kunitaro who became the parents of Nagato Hiroyuki and Tsugawa Masahiko, both of whom became well-known actors in film and television. Nagato himself can symbolize much of Japanese film history. As a child actor, he appeared in The Life of Matsu the Untamed, the original 1943 version of "Muhomatsu no issho" directed by Inagaki Hiroshi that is a masterpiece of pre-1945 cinema. When he grew up, he became a crucial actor in the postwar transformation of Japanese cinema, starring in such works as the taiyozoku film Season in the Sun and Imamura Shohei's New Wave masterpiece, Pigs and Battleships. He has continued to play a variety of odd and interesting roles in the films of many directors, such as Miike Takashi's Gozu

.

Tsugawa also appeared in some crucial Oshima Nagisa films as well as in Crazed Fruit. In recent years, he has taken up the megaphone and directed a number of films using the name Makino, such as Wakeful Nights

(in which Nagato appears).

Both of the brothers married famous actresses. Nagato married the wonderful Minamida Yoko (who passed away in 2009, after a long illness during which Nagato took care of her - a role that earned him increased media attention in the last few years) and Tsugawa wedded Asaoka Yukiji.

Now that Nagato has passed away, it seems like a large chunk of Japanese film history has gone with him. One of the Makinos (Masahiro's son) runs the Okinawa Actor's School, but there is not really anyone young in the family on the small or big screen anymore (except for maybe Mayuko, Tsugawa's daughter).

I wonder if Nagato will be buried in the family plot, located in the Tojiin temple graveyard in Kyoto. There's a huge statue of Shozo there, because one of his studios was actually on the temple grounds. Matsunosuke's grave is in another Tojiin graveyard inside the Ritsumeikan University grounds. Perhaps I will do ohakamairi the next time I am in Kyoto. Such an actor - and such a family - should be honored.

The newest issue of

The newest issue of  I

I