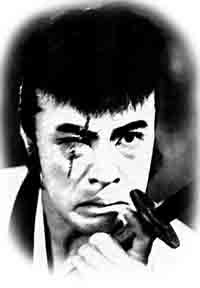

Kojiro

This is not film news per se, but rather a memorial in virtual space for a departed loved one.

Yesterday evening, April 27, our tabby cat, Kojiro, was killed by a speeding car just two houses away from us. It was quite a shock, in part because our life with this mysterious cat was quite short-lived. He just showed up on our doorstop one rainy November night last year, and kept coming back until it seemed he had chosen us for his new family. He stayed indoors for most of the winter, but come spring, he would run outside and sometimes not come back at night. He wasn't the most attractive cat, yet he was very friendly - but he rarely ever purred. A very contradictory creature who was quite an individual. Only a bit over a year old, he left us all too suddenly.

Kojiro came to us like a wandering samurai, so we named him after Sasaki Kojiro, Miyamoto Musashi's legenday opponent popularized in the Yoshikawa novels and in various movies, and played by such cool dudes as Tsuruta Koji and Takakura Ken. (Our cat just did not seem someone we could name Musashi.) There's even an eponymous 1967 Inagaki Hiroshi film on this rather tragic figure starring Onoe Kikunosuke. I wonder whether we shouldn't have given him a more propitious name, although we more often called him by his nicknames Obojo and Obo.

Kojiro had one other media connection: he was an inveterate kotatsu neko. One of my favorite characters from Takahashi Rumiko's Urusei yatsura is Kotatsu Neko, the ghost cat who comes to haunt Ataru's kotatsu because he had been kicked out of a kotatsu when he was still alive. (A kotatsu is a heated table popular during Japanese winters - ours was handmade by Ohdera Yasuo of Jin Woodscapes.) Well, Kojiro loved our kotatsu and spent as much time in - and sometimes half-in and half-out - of that heated space as he could. It is strangely appropriate that he passed away right after we put away the kotatsu for the year.

Perhaps he will come to haunt us next year? If he does, he will be most welcome. Kojiro was a strange creature, but one who was much loved.

Kotatsu neko Kojiro half out of the kotatsu.

We would call Kojiro "Kanai-san" when he donned this hat.

Kojiro certainly measured up to the cats I know - on his own individual scale.

Sayonara, Kojiro.