A few days after Sakamoto Junji visited my Yale Summer Session course, Matsuoka Joji came by to show his film from 2007, Tokyo Tower: Mom and Me, and Sometimes Dad (Tokyo Tawa: Okan to boku to, tokidoki, oton) and talk about his experience as a director.

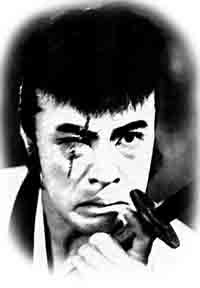

I've long been a fan of Matsuoka and somewhat disappointed he hasn't gotten the attention he deserves, especially abroad. Bataashi kingyo was one of the first films I saw when I came to Japan in 1992 and I was impressed enough to later include it in my "Best 30 Japanese Films from 1989 to 1997" that the intellectual journal Yuriika (Eureka) asked me to pick a long time ago. I have not liked every single one of his films, but that is in part because he had for a long time been on the lower rungs of directors in the industry and thus the one that producers called later on or for lesser, more formulaic projects. He himself told the class that he had his own career crisis before even starting. After graduating from the film school at the Nihon University of Art, and winning a couple of awards at the Pia Film Festival for Sangatsu (1981) and Inaka no hosoku (1984) (incidentally, both starring the girl, he told the class, he started making films in order to get to know, but who ended up going out with the lead actor), he still was at a dead end and, while experiencing a little mental crisis, thought of giving up filmmaking. It was only because it was the bubble era and companies had money to throw around that a producer who liked his Pia films suddenly called him to offer him Bataashi kingyo. After that, he got a range of work from minor TV money productions to the very low budget Akashia no michi.

But in all his work, he proves himself to be not only an expert at the craft of cinema, but also a master of depicting complicated human relationships on film with subtlety, intelligence, warmth, humor, and reality. Kirakira hikaru is about a homosexual triangle and Akashia is about a daughter who has to care for an increasingly senile mother who abused her as a child. I once showed Akashia no michi at a Yale symposium on aging in Asia and all the participants raved about it, hoping that they could use it in class, but none of Matsuoka's films have been released abroad on DVD. The only ones out with English subtitles are Sayonara, Kuro, a wonderfully emotional film about a dog and the students who care for him (the Japanese DVD has subtitles, but I think is now out of print), and Tokyo Tower (which is available from Hong Kong with English subtitles).

To show my students the difference an expert director can bring to a story - and in some ways to show the difference between much Japanese television and good Japanese cinema - I showed the class the scene where Okan dies in the TV drama version of Tokyo Tower starring Hayami Mokomichi and Baisho Mitsuko. The difference between that and the same scene in the movie was incredibly clear. While Matsuoka reduced his scene to a number of shots, with barely any analytical editing, and cut away just when it was getting emotional, the TV used every visual trick in the book in excess, milking the scene for everything it could. Matsuoka, who was seeing a scene from the TV version for the first time, couldn't believe it: "It seems like a bad joke," he commented. To him, the scene had no reality and he proceeded to explain how he aimed for reality in his version. For instance, he insisted on casting Odagiri Jo as "Boku" from the start in part because Odagiri was very much like Boku: he was raised by a single mother in the countryside, came to the city, and later invited his mother to come too. It just so happened that Odagiri's mother was in the hospital when Matsuoka first approached him, and at first rejected the offer because it too greatly resembled his reality. Odagiri also invested a lot more in his role than Mokomichi did (or could have done, given the lack of time "tarento" are given to prepare anything on TV). Matsuoka impressed several students with an anecdote about one scene - the one where Okan wakes up a night in the hospital and is hallucinating - where Odagiri had to meditate for over an hour on the set because he could not get into the mindset that saw Kiki Kirin (who played Okan) as his mother, especially since the previous scene did not go that well. One doesn't get that on the TV drama set. (I was, by the way, fortunate to be able to visit Matsuoka's genba when he was filming Kanki no uta.)

Students also asked about the prominent use of voiceover narration in Tokyo Tower, a technique he has rarely used in his other films. Matsuoka is skilled at cinematic understatement because he refrains from the excess explanation voiceover and other techniques can bring. The voiceover in this film, however, specified in the script by Matsuo Suzuki, was quite different. First, Matsuoka said he put a lot of effort into recording it. It was done after the film was all edited: he would show the movie in 20 or so minute segments to Odagiri and let him think and get into the mood before recording. This was done over and over and, for a film about 150 minutes long, took a long time to do. I also pointed out how the voiceover often functions to head the melodrama off at the pass: for instance, during the funeral, we don't see Oton cry - one would think the most emotional part of that scene - but Matsuoka just cuts away and lets the voiceover briefly mention the fact. The voiceover thus allows him to tone down the emotional power of the image, or even to cut the image away and bridge the resulting gaps in a minimal fashion (as he does when Boku first meets Mizue: in the image we just see them sit next to each other at a bar, each not noticing the other, and then the film cuts to them walking together weeks later, with the voiceover briefly mentioning that he found a girlfriend).

My students were a little tired that day (their final papers were due then), but many later wrote in their comments that Tokyo Tower was one of their favorite films of the semester - in a course that included movies by Ozu, Mizoguchi, and Kurosawa. I was glad to hear of their appreciation of a director who definitely deserves more appreciation. Matsuoka-san has a new film coming out in December entitled Snow Prince. It looks like another potential "tearjerker," but knowing him, it will probably be done with subtlety and art.