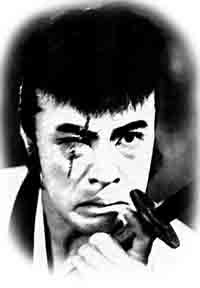

Kurosawa Kiyoshi

The second director to come to my summer class was Kurosawa Kiyoshi. Kurosawa-san and I go back a couple of years: we were first introduced by Aoyama Shinji, but I only had a real talk with him when I interviewed him after Bright Future. He kindly came to Yale in March 2006 when we hosted Kinema Club and gave a workshop on film (he mostly discussed other directors) and commented for a panel on Japanese horror. I think this was the first time I've seen him since then. We showed Cure and again went out drinking afterwards (this time to a better place).

As some students noted, on a personal level Kurosawa-san is a marked contrast from Hiroki-san. They are about the same age (Hiroki-san is one year older), but whereas Hiroki-san wears funky t-shirts, hangs out with young people, jokes around, and quickly answers questions, Kurosawa-san wears conservative clothes, tends to be serious (without being stiff and formal), and thinks very carefully before answering. In terms of translating, Kurosawa-san is a lot easier to interpret for because he is quite measured in his speech.

Still, I remember going out drinking with Kurosawa-san after the screening of Loft at Yale. I think he was quite nervous before the screening about how the audience would react, but the good comments he got (one of my students made a great observation about the "anxiety of influence" in that film), coupled with the two-foot tall glass of beer he had, made him visibly relieved. It was nice to see a looser Kurosawa-san that time.

I think he was also quite relaxed this time around too. He confessed he had not talked about Cure in a while, so he could not answer every question the students had, but I think he, like with Hiroki-san, did make them think a lot about how to create cinema that does not ram explanation down the throats of the audience. He was especially interrogated about the scriptwriting process and his relations with producers. He emphasized his belief that the ambiguity in his films stems not only from his own, honest inability to provide clear answers, but also from a central ambiguity in cinema compared to the novel. I then queried him about the novelization of Cure that he wrote, noting, for instance, that the end is "clearer" in the novel than in the film. He laughed, and commented how novels allow you to lie better than cinema does.

It was nice to have these two directors come to class. I can occasionally rope in a visiting director or two when I am at Yale, but teaching in Japan allows for a lot more contact with filmmakers and the industry. The summer class this year was pretty tough (it was too hot to lead students around on field trips!), but quite rewarding.