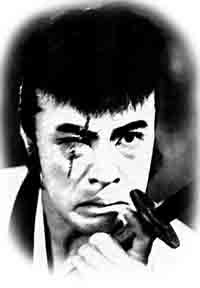

Takamine Hideko

Deko-chan has passed away (here's one story), and with it, a brilliant life in cinema.

Takamine Hideko was always one of my favorite Japanese actresses. As a child star, she was as adorable as could be, as a teenager, as cute as could be, and as an adult, as beautiful as could be. She was a remarkably versatile actress, one who quickly transitioned from precocious children in films by Ozu Yasujiro (Tokyo Chorus), to cute girls in Makino Masahiro (Awa no odoriko or Hanako-san), to dramatic powerhouse in Yamamoto Kajiro (Tsuzurikata kyoshitsu or Uma) -- all before she even hit age 15. As an adult, she was most famous for the dramatic works of Kinoshita Keisuke (Twenty-Four Eyes

) and Naruse Mikio (When a Woman Ascends the Stairs

; her face at the end of Midareru is one of the most powerful visages in film history and graces the front page of Catherine Russell's The Cinema of Naruse Mikio

), but we should not forget her great talent for comedy (playing a stripper in Kinoshita's Carmen Comes Home or a conniving housewife in the satirical Fuzen no tomoshibi) and for singing (Ginza kankan musume). She seemingly could do everything, and do it with resolve and bright inner strength. After retiring as an actress, she even excelled as a witty essayist, publishing nearly a dozen books.

She will be missed, both publicly and personally.

This is Deko-chan singing "Ginza kankan musume":

Eiga to iu tekunoroji keiken 映画というテクノロジー経験

Eiga to iu tekunoroji keiken 映画というテクノロジー経験 Itagaki Takao: Kurashikku to modan 板垣鷹穂 クラシックとモダン

Itagaki Takao: Kurashikku to modan 板垣鷹穂 クラシックとモダン